Tales from the Gap

Annual Squadron Tests

There I was. It was mid-January 1964, and my platoon was stalled in the middle of a small German village. The entire 1st Squadron was motionless behind us. In front of me was Lt. Col. William L. Webb, my squadron commander ordering me to put my helmet on and tell him what was happening. I told him that my lead M114, a scout vehicle of ill-repute, had stalled and blocked the narrow village road. It was a story he had heard may times during his command. A snowstorm on the east coast delayed by a day my flight from the U.S. to Germany and my signing-in to the 14th Armored Cavalry Regiment in Fulda. But 36 hours later I was commanding the 1st platoon in C Troop and leading the 1st Squadron on a road march at the start of its annual test. Fortunately, the platoon had skilled NCOs who quickly cleared the M114 from the road and had the squadron on the way again. Little did I know then that my two years in the squadron would be the most formative, interesting, and challenging two years of my life (from age 22 to 24). I owe much of my beliefs and values to those years, particularly to the 21 months I led the 1st platoon.

By the night of that first day there had been numerous complaints about vehicle communication problems. The radios were new, radically different from the old ones and had been installed a short time before the test. But fortunately, they were the same type radios I had recently learned to use at the Armor Officer Basic Course at Ft. Knox where I was a student before coming to 1/14. So, I went my other vehicles–four M114s, two M60A1 main battle tanks, an M113 Infantry carrier and XM 113, 4.2 mortar carrier–and conducted individual instruction for the crews. The commander’s model featured ten push button frequency selections and was mounted just inside the commander’s hatch. It was very easy to knock buttons out of whack by simply getting in or out of the vehicle or moving while standing inside. Conducting those sessions was one of the best things that happened to me. I showed a bit of expertise about something and the platoon members had a chance to size me up.

The next day we awoke to dense fog. London, pea soup dense fog. We were on radio silence and couldn’t see more than five or six meters ahead. I finally decided to obey the orders established the night before and move forward until we encountered the aggressors. As it turned out that was the headquarters emplacement of a regimental size unit. At that point, since we were close to them and had our weapons trained on whatever or who ever we could find, I broke radio silence and reported in. Turns out the entire exercise had become snarled by the weather. Everything was halted for more than a day to untangle. The rest of the test went as planned; I think. Who at platoon level really knows?

A year later, on our annual test we had to pull our tanks, each weighing 53 tons, out of the maneuvers. The warmer-than-usual weather turned roads and fields into muck and mire. The tanks kept sinking in the mud, sometimes to near the top of the tracks. This exercise featured the longest stretch of time I ever spent executing tactical maneuvers.

We’d been out about a week when C Troop was ordered to establish a position overlooking an area, including a road intersection, where the aggressor was expected to make a push the next day. We’d been going hard that entire day. My scouts finally found a good overlook on which to set up. I had an artillery NCO assigned from a level above Regiment. We spent much of the night huddled in my M-114 pre-plotting targets and registering them with the battery supporting us.

The push came early the next morning and my platoon succeeded in stalling a squadron/battalion sized unit. The maneuvering went on for most of the day. We were finally ordered to hold as 2nd platoon on our left and 3rd on our right withdrew. We then were ordered to execute the retrograde and passage of lines in fading daylight. That can be one of the most difficult and dangerous maneuvers during a fluid situation. We had to move the platoon through friendly lines of another unit, not part of the 14th. In combat if not done properly it could lead to a full-scale fight.

Who knew the simplest of things would foul us up? We headed along the route we’d been given to refuel and re supply when we came to a village we needed to pass through. As planned, we were met by an officer from the unit we had passed through. He had reconned the village and decided the main street was passable. He was wrong. As our lead scout vehicle moved in, the sergeant in command quickly determined the streets were too narrow for our tanks. It was almost dark, and we had to back up the entire platoon and find a way around the village.

We made our way to the resupply area. In total darkness we had to refuel our vehicles while feeding the platoon a hot meal from the mess truck. Our refueling was a bit complicated since our tanks required diesel and the other vehicles gas. The refueling points for each were in different areas. Add deep darkness in a forest and it became confusing and sometimes hazardous. We were using flashlights to ground guide the vehicles. For tactical and safety reasons all vehicles’ lights were on blackout. There were some quick starts and stops and a near collision, but the entire troop made it through. We were then ordered to an assembly area. We arrived about midnight and set up a perimeter. Most of the troops were finally bedded down when, after 36 hours with little sleep, orders came to move out and quickly set up a screening action.

It was brutally cold, and we were all tired. As we were moving down the road, my head sticking outside my M-114 hatch, I actually fell asleep. I was awakened by the voice of my driver trying to explain, via radio, to our Troop operations how the platoon leader (me) could be rolling down the road, but not be there. My driver was trying to cover my ass.

Shortly before sunup we arrived in position. I sent my scouts forward to set up surveillance. A short while later I got a call from one of my scout leaders saying he was on the way back with a captured aggressor. It turned out to be a platoon sergeant. My scouts had set up an ambush in a village and managed to trap an entire platoon. In all we went over 40 hours with little or no sleep. Yet we operated efficiently, accomplished the mission above expectations and did so while driving heavy vehicles through the dark and cold without significant incident. Except for my driver trying to protect me.

Shortly after that the tanks were pulled from the exercise. We barely escaped getting one tank badly mired in the muck. The tank troop managed to sink a couple that required a Tank Recovery Vehicle to extract them. Without competent NCOs and some highly skilled enlisted men, very little of what we did for the 21 months I was a platoon leader would have been possible.

What was to be my squadron third test was spent as an assistant S-3. That one, which I wrote large parts of, had to be cancelled or postponed because of even warmer weather than the year before. I didn’t know which because earlier (on February 5th, 1966) a fellow officer, who was in Delta Troop (the tank company) and I, having finished our stints in the Army, began a nearly six-month sojourn in Europe in his VW Beetle with two sleeping bags and a single burner stove. It is something we had talked about doing since meeting at Ft. Knox.

The Border

Shortly after the squadron test, I headed out for my first border patrol. We road marched to the Squadron Observation Posts overlooking East Germany. I tried to apportion border duty among my soldiers so each would have the “border experience” at least once before leaving the squadron. Probably more for their grandchildren but still it’s good to know the territory you may have to fight over.

If the Soviet forces had attacked, our battle would have been short lived. The Cav troops would have taken the first onslaught and been badly outnumbered. Estimated time of being a useful fighting force was about 24 hours. Finally, when reduced to uselessness the fall back was to try making our way to Frankfurt. Survival was a long shot. This was the punctuation point to our regular briefings, usually by the troop commander, about our mission, held in a secure room, which even in the winter became insufferably hot. We were invariably down to T-shirts by the end.

The Fulda Gap was defended by NATO forces because it was deemed the most likely place Soviet forces could quickly cross the border in mass and still accomplish their mission: take control of Frankfurt am Main. The plans were to harass and delay the Soviet forces. It was discovered years later that a battle would develop into a nuclear battle (Fulda Zeitung, Nov. 1, 2019). The north had more open space, but it was a longer way to Frankfurt. So, there we were, the highway of choice.

When occupying the OP we used positions hidden in the woods and dug into the hillside. No fancy guard towers in 1964 and ‘65. The positions provided views well into East Germany. They were not, however, hidden from the German border guards on patrol or occupying the watch towers across the mine fields. In fact, many years later while working at the University of Utah I met an East German medical technician who had emigrated to America. He said he had been a border guard in those years and that all our positions were clearly visible. All I can say is those guys weren’t invisible either.

We relieved the platoon in place and assumed responsibility for the first squadron sector. During my 21 months of border patrols we used every vehicle in the platoon (except the tanks) when on border duty.

The border officer’s basic job when on patrol was to traverse the entire north-south length of the squadron’s area of responsibility, or sector, and look for and report any unusual activity on the Soviet/Warsaw Pact side. It’s easy to think the border was marked by a minefield fronted by barbed wire. In fact, the border markers were two-foot-high concrete pillars sticking out of the ground. Anything beyond that was the Soviet territory. The barbed wire was generally ten to 25 meters back from those pillars. If you got close to the wire you had crossed the border.

My jeep driver on that first patrol was from Southern California. He had never been in snow. Regulations prohibited having tops on our jeeps. No one ever explained why, but the most logical explanation was severely obscured vision. The tops with their canvas sidings punctuated by severely scratched and discolored plastic windows were useless. However, the missing tops meant another form of vision interruption–the Army arctic parka. When standing they hung down to just around knee level. The wool-lined hoods swallowed your entire head, and whether looking left or right you only got a clear view of the hood’s interior. As we crested a slight rise in the road and started down a slope, the jeep began to fishtail. My driver had lost control. Every time I looked toward him, I saw only my hood. I told him to get off the brake and down shift. No response. A louder voice did not help. Finally, the jeep 360ed into the right roadside ditch, coming to rest at a 45-degree angle with me on the downside. The stop was jolting, but no injuries. I ripped back my hood and turned to my driver only to find no driver. He had jumped out near the top of the hill. I looked back and saw him laughing. I wasn’t. My infantry squad leader had been thrown out of the back. Both were okay. So was I, but the laughing didn’t sit well. In fact, it pissed me off. The sergeant intercepted me before I got to the driver. He called one of our scout vehicles to be sent out from the OP. It was able to pull us out. It also contained an extra occupant, who took over driving duties.

The next day another platoon member was driven out from the kaserne to drive my jeep. He remained my driver until I left the troop. Gary Batchelor was a PFC from Arkansas, not a place known for its snow. But he had a natural ability and developed an instinct allowing him to understand what was needed not only as a driver, but also as a valued assistant.

Driving an M-151 jeep was not something anyone came by naturally. They had a high center of gravity, a steering wheel not much smaller than a wagon wheel. Manually locking them into four-wheel drive was time consuming. That pretty much sums up my first month or so in the Fulda Gap.

Cold Weather Gear

This is as good a place as any to talk about cold weather haberdashery Army style. The parka was fairly functional and effective. Other items had their challenges. We were issuedarctic mittens, well-insulated items which engulfed your hands and reached halfway up your forearms. They and were connected to one another by a strap that hung around the neck. They were good at keeping your hands warm. But pulling any sort of trigger while wearing them was impossible. It was also impossible to write with them on. If writing were necessary, off came the gloves. About halfway through taking notes hands became blocks of ice. After that, not even wearing the mittens for a long time sufficiently re-warmed the hands. While working from a jeep, a hand microphone was used to operate the radio. So off came the mittens again. Then back on. Another piece of cold weather gear that was debatable was the arctic hat. The outside was a heavy material, the inside wool. There were earflaps that tied upward over the head. To warm the ears, flaps had to be untied, pulled down and the strings retied under the chin. Meantime the hands were outside the mittens being re-frozen.

We were also issued wool shirts. Between these and the wool caps, more commonly referred to as “bunny hats,” the wearer soon began itching from waist to head. Scratching was cumbersome and, with the arctic mittens on impossible.

The last item of warm weather gear we were issued were thermal boots, unpopularly known as “mouse boots.” They were rubberized and reached about halfway up the lower leg. They looked like Mickey Mouse’s feet. Inside there was an inner sole, under which was a pocket of air over the outer sole. The air acted as insulation. The warmth was generated by body heat from the feet. Walking was more like clumping. And we did more walking than ever imagined when I listed Armor as a branch of choice. Stop walking and the perspiration began to get cold and could lead to frost bite. The solution was to change into a dry pair of socks, which we were all admonished to carry. The result at the end of the day we had cold feet, two pairs of damp, cold socks and funny looking boots on our feet. Imagine trying to dismount an armored vehicle with all this on. When walking you made Dr. Frankenstein’s monster look like a ballet dancer. The solution was to take the socks into your arctic sleeping bag so they would dry out overnight. The reality, we mostly slept in our vehicles wrapped around racks and boxes of ammunition, trying to pretend our commo helmets were pillows. The mouse boots were shoved into a corner or tied to the outside of the vehicle. Tanker boots, or even regular combat boots were more comfortable and could be fairly quickly removed to change socks. The used pair could dry when placed on the grating over the engines when we were stationary. Engines idled almost constantly to keep batteries charged and radios operational.

Border: New Year’s Eve 1964

My driver, PFC Bachelor and I were wrapping up 16 cold hours of patrolling near midnight and making our way back to an OP above Tann. The town, really closer to a village at that time, was located in a salient. This meant it was bordered left, right and front by East Germany and the minefields. We had to go through town and connect with a trail that took us up a hill to our OP. As we drove into town, doors burst open and villagers poured out onto the main street toasting New Years. They blocked the roads and wouldn’t let us through until we joined them in a couple of toasts featuring the requisite prosits and a few rollicking neue jahrs froliche.

Remembering the admonishments to maintain good German-American relations at all times I joined them. My driver stayed alcohol free but did a little frolicking. He obviously had more important things on his mind, like our safety. It was a nice way to end the year.

Goose Feathers and Fire

November of 1964. During a particularly cold stretch my driver, PFC Batchelor, and I were on border duty. We had gotten delayed waiting for a contact to arrive at the designated checkpoint. We had regular contacts with the German Border guards, the German customs police, and the two other squadrons of the 14th that flanked us on the north and south. When we finally arrived back at the OP it was cold, dark, and late. I was suffering from a bad cold that seemed to only get worse as the day wore on.

The OP consisted of a squad tent with cots for off duty soldiers to sleep on. Everyone had been issued Army arctic sleeping bags, which were surprisingly sufficient in most circumstances. Before we headed to the tent, I stopped to check in with in with Sgt. Banks who was in charge of the OP. He was in a portable radio shack that featured a Yukon stove for warmth. I must have looked horrid. He immediately suggested I sleep in one of the two cots in the shack instead of the tent. After some resistance I accepted. I got my sleeping bag threw it out on the cot nearest the stove then stripped out of my arctic wear and crawled in. I fell asleep immediately, only to be awakened sometime later by the bottom of my sleeping bag going violently up and down. I came awake and was greeted by the sight of goose down flying all over the place, and Sgt Banks vigorously shaking the sleeping bag. It was on fire. I scrambled out and he got the fire extinguished. We saw and smelled goose down all over the place. The fire had started when straps on the bottom of my bag had flipped over on top of the stove. The remnants of the sleeping bag spent the rest of the night in the snow.

I got dressed, hiked up the hill to the squad tent, threw someone’s sleeping bag over me and went to sleep. Before I left in the morning for my first contact I checked into the hut. They had pretty much gotten things cleaned up. I threw the remains of my sleeping bag into the back of the jeep and we motored off. The next night we slept at Wasserkuppe, which I generally tried to do as often as possible when on border patrol.

A week later I got a letter from my mother saying she had been in church on my birthday and said a prayer for me. That was the same day my sleeping bag went up in feathers. I wrote back saying her prayers, while appreciated, apparently went in the wrong direction, maybe she should give it up. There was no response.

Wasserkuppe

The Wasserkuppe was (and may still be) a recreation area. It is on top of a plateau and ideal for flying gliders, hiking and other recreational activities. In the winter it featured a plattepulle ski lift. It is the same as a T-bar Americans are used to, except in place of the iron crossbar there is a disc. When it’s your turn to get on, just grab the moving bar hanging down from the cable, stick the disc (platte) between your legs and off and up you go. Get off at the top. Ski down. Repeat. As are most skiers in the American Intermountain West I’m am a bit of a ski snob or was. So, after a day of Wasserkuppe, I gave up skiing for the duration.

More important to those on border patrol during the Cold War years, there was a U.S. Air Force radar station there. On the third floor of one of the buildings we had a radio relay station. It ensured decent communications between Border Ops in Fulda and our outposts. But more importantly to us it had a sleeping room with bunk beds. Despite the urine smell seeping up from one of the two floors below us, it was a more comfortable place to sleep than the OP. Best of all there was an Air Force mess hall where you could get a good breakfast and even dinner if you got there soon enough. As an officer I was supposed to pay for my meals, but they refused to charge me. Pity is not always a bad thing.

Border Dangers

Many roads meandered through the countryside and across the border. These were generally marked by barriers. These were on the West German side. Inevitably beyond it was the omnipresent barbed wire fence. As we approached one such barrier, I heard an explosion. Neither my driver nor I could see where it came from, but it sounded like it was from the right, beyond a small, wooded hill.

I grabbed my binoculars and climbed up through the woods. As I cleared them, I saw some East German soldiers working in the mine field. A minute or two later there was another explosion showering dirt and rocks down on top of me. I think they were destroying old mines.

What I didn’t realize until I got out of the woods was that I had been across the border. I called the incident in to border ops and they said they would try to get an over-flight. I never saw one. Nor did I hear whether someone discovered what had happened. And “they” never found out I had been in East Germany.

Who Are We Guarding Against, Anyway?

During a border patrol I got a call from my OP commander saying there was a sergeant claiming to be the senior NCO in the squadron S2 (intelligence) section. He wanted access to the OP but claimed he forgot the password for the day. I said several times no password, no entry. Same result. I asked the OP NCO if he was armed. The response was “affirmative.” I said, “lock and load and explain that he has two choices either leave or wait for me to get back in about 20 minutes.” A few minutes later the NCO said, “He left, but said he’d be back.” I said, “okay and you know what to do if he does.”

He did not return the following day, but one of majors in the squadron did. He tried the same gambit. This time I had him held until I got there. Upon arrival he told me to let him in or I would be in big trouble. I said not without a password. He tried to move in anyway and we repeated the lock and load. He kept insisting. I ordered the guard to rack (chamber) a round. He did. The standoff ended and he drove away. I assured my NCO and the guard there wouldn’t be any repercussions. There weren’t.

Following another border stint, we were heading back to the kaserne when I got call to be ready to stand inspection at 0900 the next day. When I got in I found out we were to be the lone platoon on display and the inspectors would be V Corps Commander, Lt. Gen James H. Polk and a French five-star. The obvious question was why us? There were eight other reconnaissance platoons in the squadron. As far as I knew they had just been sitting in the kaserne the entire time we were on the border. I got no answer. This was a trap. V Corps had been on our butts for M114 maintenance problems. Why pick a platoon that had elements on the border with little or no time to do even routine maintenance and had just performed a road march to get home? No answer, just do it.

Well, the platoon members back at the kaserne had already gotten the remaining vehicles, two tanks, one mortar track, the infantry track and my M114 cleaned up and looking good. In order to put some extra “spiff” on their exteriors the NCO in charge concocted a mix of flam-

able fuels to cut the dirt. It did the trick. It also made the surfaces extremely slippery. Rinse as they might that could not be changed. So we had four mud-splattered M114s and a jeep that needed to look like the other vehicles. After a discussion I said, “give them the same treatment.” They did and within a few hours of all hands-on deck work we had them looking good and slippery. It was getting dark when the squadron commander came out to inspect. I’m praying to myself, “please don’t try to get on a vehicle.” No answer. He approached one tank, gripped the steel outer frame around the left headlight, put his foot on the front slope and tried to hoist himself up. His foot slipped, but not badly enough that he fell. He paused for a minute. He knew what had gone on. He walked around the entire platoon, came up to me, said good job and headed back to his office.

The next morning a helicopter landed on the parade ground. I approached, saluted, and led the inspecting party to my platoon. I explained each vehicle, answered questions. After we circled the platoon, we chatted a bit more then headed toward the chopper. Gen. Polk, said “good job lieutenant, but I think you overestimated the armor penetrating range of your .50 caliber machine gun.” I saluted and said, “thank you, sir.” But I was thinking thank you for not trying to climb one of the vehicles. He was a former Cavalry officer, both horse and armor. The party then headed off to discuss the real business of the day, our maintenance problems.

Tank Gunnery: Wildflecken

Several weeks before going to Grafenwoehr, the large training base in Bavaria for tank gunnery, we road marched to the fairly nearby firing range of Wildflecken. There we went through training and testing on all weapons. This was the only place even remotely close to us that had a range big enough to fire the main 105mm tank guns. Even at that we could only fire the HEP (high explosive plastic) round. It had the lowest velocity of the three types of main gun ammunition we carried. The other two types were HEAT (high explosive anti-tank) and SABOT (armor piercing discarding sabot). It was so fast we never fired it. It didn’t take many rounds before the grooves inside the gun tube were worn to the stage that it was unusable.

On my last trip to Wildflecken it was decided, not by me, that I should command, the first tank down range for Table 8B. It was a night test requiring identification of targets, properly engaging them, selecting the proper weapon, hopefully hitting the target then moving on, searching for other targets. 8A, the daytime test and 8B were the last two exercises in gunnery testing. The scores determined success or failure and stuck with crews for a year. When we finished we felt we’d done well. But upon arriving at the debriefing tent there was a definite air of gloom among the staff. Turns out, rumor had it, that the word had gone out to all graders not to pass any crew. We had come close to maxing the course. I don’t know if our grader didn’t get the word or what happened. The philosophy was apparently to make us sharper, by not letting us succeed.

No one passed that night, including us. We took our second run and when we came to our first target, which required the tank commander (me) to engage it with the cupola mounted .50 caliber machine gun. A nasty weapon. I dropped down through the hatch found the target in my night sight. I fired but I saw no hits or tracers. Figuring I was high I cranked down. Again nothing. I cranked it all the way. And saw rounds hitting about twenty meters in front of the tank.

The driver was immediately on the intercom yelling “up, up.” I decided it was best to move onto the next target. That was the only .50 caliber engagement that night.

After finishing we pulled off the course and into the tank park. I immediately kicked on the lights inside the turret. It didn’t take any time to see the problem. The alligator clip that connected the .50 caliber sight to the weapon was disconnected. My supposition was someone did it while we were in the debrief to make sure we failed the second run. However, it had been my responsibility to run through the pre-firing checklist and I hadn’t. We were the only ones to pass that night.

Grafenwoehr: Road March & Advance Party

Grafenwoehr is a main training area for U.S. Forces and other allied countries. It is located south of Fulda in Bavaria. On my second tank gunnery experience I was the Squadron’s wheeled convoy commander. That meant I also acted as the Advanced Party Commander upon arrival. It was a full day’s drive. I still haven’t figured out how all those vehicles in a column, travelling at the same speed can be bunched in the front and strung out in the back. We all arrived safely. I’m not sure about all the German motorists who disobeyed our “mox nix” sticks and chose to weave in and out of our line wheeled vehicles of all types from every unit in the 1-14. “Mox nix” is a bastardization of the German “mach nicht.” They were a round disc on a stick. On one side was the international road sign for don’t pass, on the other a passing sign. It was the mandatory job of the vehicle commander to indicate to civilian traffic approaching from the rear when it was safe to pass and not safe to pass.

I also was in charge of the advance party. I made sure all on post facilities and equipment we would be using would be turned over to us in good shape, knew where our initial firing ranges were and the location of our assigned motor pool.

Grafenwoehr: By Train

On my last Graf trip, I was the train commander. All of our tracked vehicles went to Graf by train. Loading the tanks took time and skill. They were a bit wider than the flat cars. If not precisely loaded so the overhang was equal on both sides they could hit a tunnel wall. The German rail people were demanding. A couple of times a tank had to be backed off to start the process over. It was a long exacting operation. In spite of all the care taken, I still held my breath and felt my spine tingle when we went through the first tunnel. I quickly learned to have faith in German rail officials and their calipers, micrometers and whatever other measuring devices they used.

We were a low priority train, so it took us over a day to get to Graf. We spent time on rail sidings watching passenger and freight trains whiz by. But inside we were a high priority. The train was manned by a German crew. All white linens and German cuisine. For many of our soldiers, train travel was a new experience. It was only my second train trip. I love sleeping on a moving train. This was the only time our vehicles did not carry their usual combat load of ammunition. We stored it in Fulda and drew ammunition at each range we used.

In the first week of my first Graf experience, I was assigned as a range safety officer. The main guns were firing. It was night. I had to ensure no one fired outside the range limits and look for violations of other range safety rules. That night there was a main gun misfire. The range was shut down while I attempted to get the round to fire. Failing that I had to extract 105mm tank round and carry it to the misfire pit. I dropped the breach. The back of the round had a scorch mark. The electrical circuit needed to ignite the round had been completed. The round should have fired. I turned the round 180 degrees and slammed it back into the tube that automatically closed the breech. I ordered the gunner to fire. Nothing.

The next step was to extract the round. I slowly pulled the heavy hunk of brass and explosives out and pushed it up through the hatch to the loader who was standing outside on the tank fender. I then scrambled up and out of the commander’s hatch, down to the ground went around the back of the tank to the other side and took the round from the loader who was eager to get rid of it. It was presumably live and still capable of going off at any time. Getting it this far in the procedure was stressful enough. But this was at night under blackout conditions. I had rehearsed the walk to the misfire pit during daylight, but other than give me a sense of direction, the practice wasn’t much use in the dark.

I was getting close to the pit when I hit a road berm. I stumbled slightly when an explosion went off. I thought I was dead. The range officer, who was supposed to wait for the all clear from me, had resumed firing. Recovering, I carefully crept across the road, down the berm on the other side, found the misfire pit, and gently with the business end of the approximately 32-inch round facing down placed it in the pit.

My next stop was the control tower. I climbed up, opened the door and started to ask a rather impertinent question when I remembered the range officer was my troop commander. I left without a word and we never talked about it. Lessons learned by both parties. He should

have waited; I should have kept him better informed of my progress. But in my defense, I had been alone, with no radio and even if I had one, no hands free to use it. In his defense he was under pressure to clear the range by a certain time, so the next unit could move in.

After seven Tables we were fully checked out. Guns working, sights adjusted, crew primed for Tables 8A and 8B. This where the official score for each tank crew is established. It stays with the tank for a year. Table 8 consists of moving down range, identifying targets, the tank commander giving the proper fire command, engaging the targets and moving to the next one. In those days the tanks had no stabilizing system for firing. It meant the tank had to come to a smooth stop, the main gun had to be loaded, the gunner had to input the type of ammunition into his rudimentary computer, lay the sights on the target and fire. By the end of each run the main gun, coaxial 7.62 machine gun and the cupola mounted .50 caliber machine gun had been used to engage targets more than once. The “coax” was mounted alongside the main gun. The loader was responsible for having it loaded, the gunner for sighting and firing it. The .50 caliber was loaded and fired by the tank commander.

The tank would move down range until the first target was spotted. The tank commander would then issue a fire command. The command would change from target to target. The following is for firing on another tank. “Driver Stop”- the driver quickly begins decelerating to a smooth stop. No bouncing of the gun tube. “Loader HEAT” – as the tank is still slowing, the loader loads a High Explosive Anti-Tank round and yells “up” when the round is ready to be fired. The gunner is indexing the ammunition type into the computer. The tank commander is already using his control override to turn the gun tube towards the target while simultaneously giving the gunner his command. The gunner’s only view of the outside world is through his gunsight. “Gunner, Tank, 800, Fire”- this identifies for the gunner his target and the approximate distance to it. The word fire tells the gunner to shoot when he’s ready. As soon as sees the target in his sights he takes control of turret movement. The target is a silhouette of a tank. He aims at the juncture of the tank body and the turret. As he fires, he says “on the way.” To get a good score, no more than 15 seconds should elapse between the command to fire and the firing of the gun. However, the goal is eight seconds.

We also had to float our M114 scout vehicles. Amphibious was ambiguous in this instance. I was scheduled to go into “the lake” second.

Grafenwoehr: Armor Swims

I nosed up to water’s edge and was given a going over. Sort of like a Navy fighter shortly before launch from a carrier. Given the go ahead, we plunged in. The 13 tons of metal submerged completely and seemed to take its time struggling to the surface. Even when it did, there were only a few inches actually above water. We plowed across the lake in what I thought was an unreasonably slow speed. My driver assured me he was going as fast as was safe. Still there was a feeling of relief when we emerged on the other side. The insides of the vehicle were absolutely dry. It was an incident free experience but still I vowed if I ever confronted this situation I would do everything I could to find a fording point.

Clueless in Graf

It never ceases to amaze me that there are people who control parts of our lives but are clueless about what we do. One late afternoon after we’d closed the range to prepare for night firing the troop XO came up to me and said he’d gotten a call saying I was late for Squadron Duty Officer duty. I was flummoxed that given my job I would even be considered for the duty, let alone assigned to it. We spent much of the time at Graf living in tents on the ranges. Most days were long, firing day and night then moving to the next range and setting up to shoot the following day.

I cleaned up as best I could, hitched a ride to Squadron headquarters on main post and took over for a disgruntled sergeant holding down the fort. In the morning I caught a ride back to our range, about as far away as possible from central Graf. Much to my surprise a couple of days later I got a letter of reprimand from the Squadron Commander demanding to know why I had been late. In a typed response, I explained that no one had told me I had the duty, and since I was on the fringes of the range complex there was no bulletin board. The letter was written in a politely disgruntled tone. It’s the last I heard of the incident, but the letter and my reply did make it into my personnel file. Nonetheless, C Troop and my platoon finished Graf with high marks.

Marksmanship

Speaking of weapons, I was a terrible shot with my .45 caliber pistol. Other weapons I was okay with. The solution came in the person of Staff Sergeant Hunter in my platoon. His previous assignment was with the President’s 100 competitive marksmanship team. I confessed my problem. He said he thought he could help and to return Saturday. So I did, He told me to get my pistol from the armory. “How much ammunition,” I asked. He said, “won’t need it.” Hmmm. When I returned, he disassemble my pistol and went to work. In about five minutes he gave it back and said, “that ought to do it.” A few days later I drew my weapon and some ammunition and headed for the firing range, which I recall was off post. As I lowered my pistol into the firing position, it fired. Sergeant Hunter certainly “fixed” my pistol; its incredibly light trigger pull could be classified a hair trigger. After my initial surprise I showed a marked improvement.

Bugs & Germs

Following my first trip to Graf I was sent to the Army Chemical, Biological and Radiological Warfare School at Vilseck. It was a two-week course on the use, protection and treatment of those kinds of weapons. There I ran into Jon Collins, a former classmate at the University of Utah, who was in an Armored battalion located in Augsburg, just outside Munich. We spent the weekend there. It was my first experience in Munich but not my last. He had his mind set on making the Army a career. He had been an honor student and an outstanding cadet (I was somewhere below that). When he discovered I had perhaps the most sought position any junior Armor officer could have he was nonplussed. The last time I saw him was years later and he was still in the Army and a brigadier general.

Much of what we experienced and studied at Vilseck we had been exposed to in previous training such as ROTC summer camp and basic armor training. One of the things we had not learned about however was mustard gas. During the course instructors took a pin and dabbed three almost microscopic drops of it on the inner wrist of each of us. We then wiped one spot with the antidote the Army provided, the next with water, and the third we left untreated. The first one never blistered, the second barely did, but the third one blossomed into a blister that measured somewhere between a dime and a nickel. It was ugly, yellow and full of liquid. We were told not to touch them. Mine disappeared about two weeks after I returned to Fulda. I could only imagine how crippling or even lethal mustard gas could be if inhaled or it got into an eye.

Four years later I was back in Utah on a helicopter with then Gov. Calvin Rampton heading to Skull Valley in Utah’s West Desert. At that time almost a million acres of its vast landscape was home to Dugway Proving Ground, an Army biological and chemical research and test facility. Skull Valley sits outside Dugway’s boundaries and is a grazing range. An aerial nerve gas test had gone awry and killed some 6,000 sheep. As soon as we landed it was apparent that the culprit was a nerve agent. We were the first civilians allowed into the area. I was able to explain some things to the governor, perhaps most importantly that the agent used was non-persistent, meaning by the time we were allowed in, it was no longer active. I was a news reporter at the time for the NBC affiliated television station.

Alerts

Alerts were monthly occurrences that usually occurred in the early morning hours when there was minimum of civilian traffic and activity. At the sound of the alarm on the kaserne everyone scrambled to draw weapons, get to the motor pool and start all vehicles. Those of us who lived off post were notified by phone. Once all vehicles in a platoon were running with at least a driver and track commander the platoon was deemed ready. A SITREP (situation report) was radioed into troop operations. There were actually a couple of reasons for wanting to be first to the motor pool exit. One was to avoid a traffic jam at the gate. The other was the time it took to get to the troop dispersal area was closely monitored. Our alert dispersal area was in a forest close to the border.

Once an alert was called there were several options: 1- As soon as a unit was up and ready to go, it could be shut down ending the alert. 2- Move to the unit’s assigned Alert Dispersal Area before returning to the kaserne. 3- Conduct a tactical scenario which could last anywhere from one to three days. The last was rare, probably because of the amount of tactical planning and coordination needed with civil authorities and how much of our monthly fuel allotment remained.

C Troop was adept at getting up and running quickly. The only time that went wrong for us, it went way wrong. The alarm siren went off at about 0200, a not abnormal time. Unfortunately, less than two hours earlier the Troop’s officers and NCOs wrapped up a promotion celebration for our XO, Frank Mancuso, at the NCO club. To put it politely, affairs at the NCO club were more free-flowing than at the Officers Club. Let’s just say our reaction time was non-existent. The only thing uplifting about the whole exercise was the numerous ways some platoon members used to join us en-route. Perhaps the most extreme: an NCO by the roadside still dressing as he flagged down our column of vehicles.

Just as PFC Batchelor was my jeep driver for most of my time as platoon leader, Specialist 4 Robert Atkin was my M114 driver for a long stretch. I operated almost solely out the M114 whenever we were in the field. He came from a coal mining family in West Virginia. I kept trying to get him to think about reenlisting. He would have made a terrific NCO. But he was set on going home and when he was set on something it happened. One of his jobs on alerts was to check out my firearm and bring my notebook with the latest radio frequencies, call signs, passwords and code information. On one occasion, when I got to my vehicle, he was in the driver’s compartment going through his check list. The notebook was lying on my seat. I climbed in, grabbed it, and began going through my own routine. When I flipped the book open and looked down a Playboy centerfold stared at me.

Atkin and I played on the Troop C football team. Whenever I got in a scuffle with anyone he was the first to pull me out of the melee. But most of all he was a terrific soldier. I was really lucky to have two drivers who were also good people.

I never got over the sound we made while moving through towns and villages that were buttoned up for the night. The sound of our tracked vehicles clattering down cobblestone streets made quite a noise. Mingled with the sound of clanking moving parts and the roar of huge diesel engines along with a dozen other noises all reverberating off walls made a powerful sound. I loved it.

Tragedy

One payday night I was in the officer’s club (O club) when the bartender, telephone receiver in hand, asked in a loud voice if there was anyone from C troop present. I took the phone. The base clinic/infirmary said one of our soldiers had been admitted and an officer was needed. I went. He’d been in some sort of scuffle and was a bit roughed up. The medic on duty cleared him to go the barracks. The MP that had brought him in escorted him. I went back to the O club.

A few minutes later I took a second call. It was another injured C trooper. This time he was not only injured, but obviously high. The medic thought it was from something other than alcohol. He was kept overnight. I returned to the club. I was still working on my first beer.

Then a third call to “identify some bodies.” I didn’t really process what was said. I was wondering what was going on downtown. When I arrived at the clinic the medic in charge said there were four dead soldiers and asked if I could identify them? As he was taking me to the room to view the bodies he said, “it’s bad in there.” I was ushered in and saw four bodies on the floor. I was able to identify one. They had been killed when a car that hit a tree at about 80 mph.

The car shattered, the tree did not. Since they were in a car, with German license plates, driven by a German they were taken to a Fulda hospital. The four Americans were dead on arrival and

triaged. The driver soon died. Someone noticed the dog tags on one American and called the MPs. The delay in getting them to the kaserne infirmary made their body conditions worse. Three were badly disfigured and unrecognizable. I knew all four. Only one was from C Troop; he wasn’t the one I could identify.

A few minutes later the Squadron commander and his wife arrived. They had been at a formal “dress blues” event. I told him what I knew, pointed toward the room with the bodies, said, “it’s pretty grisly in there” and was about to take him to the room when his wife said, “stay here lieutenant you’re as white as a ghost.” I stayed.

I was later appointed courts officer for the C Troop soldier. That turned out to be the old cliché—a wife in one state and a girlfriend in another. There were two sets of letters. I sought advice on what to do and no one wanted to offer an opinion. I packed up his belongings and went through both sets of letters to make sure there were no cross filings and sent them off. I wrote a letter to both women. To the wife I wrote about what a good soldier he was, which was the truth. She also got all the personal belongings and paperwork. To the girlfriend, the letter took the form of a “I hope this letter doesn’t catch you by surprise” note.

Show Me What You’ve Got

My first troop commander 1st Lt. Benjamin Covington III and I were detailed to re-test an armored cavalry troop that had flunked its annual test. He said he’d hang out with his counterpart and I should pop in on the platoons at irregular times to see how they were doing. Mostly, it was not too good. They just weren’t well led. Even I as a fairly green 2nd Lt. could tell that. It didn’t take long for me to zero in on the second platoon. I found one of its tanks was wedged between the back of a house and a stone wall. I watched for a while and it was clear they didn’t know how to get it out without damaging the house. It was tight, but I thought there might be a way to get it out if only someone knew what they were doing. Clearly the platoon leader who was trying to guide it out wasn’t that person. I thought I saw a possibility, so I asked for the platoon sergeant. I asked him if he’d ever seen anything like this before. His answer was “kinda, but not exactly.” I pointed out what I had seen and asked if he thought we could take advantage of it. The tank was angled into the wall behind the house leaving a smidge of room to jockey the tank back and forth, in small increments until it was pointing straight down the road. I asked the platoon sergeant what he thought. He crawled around and looked the situation over and said it would be tight, but maybe. Then I said, “it’s up to you. Do you want to try it?” He took a minute and said, “might as well.” At this point the platoon leader who had said nothing piped up, “Okay, but if it doesn’t work it’s not my fault.” I said, “Everything about this is your fault.” The sergeant, acting as ground guide for the driver had it out in a little over a half hour.

Later that night I decided to look in on the same platoon. The other two seemed to be set up properly and down for the night. As we were moving along the road in front of the hill where the second platoon was located, I saw a tank searchlight on. The troop was under strict blackout and radio silence orders. I radioed to see what was going on and got no answer. Up the hill we went where I found that one of their soldiers had been run over by a tank and the searchlight was illuminating a medical evacuation (medevac) landing zone (LZ). The platoon sergeant arrived on the scene. We inspected the LZ and made some minor adjustments to avoid nearby power lines. A few minutes later we heard the helicopter approach. I asked if the soldier was dead or alive. He thought alive but nobody knew for sure. That’s when I found there had been no one attending the

victim. They pointed to him and I went over and knelt beside him. His hand reached out, grabbed mine and squeezed it. I thought I was going to hear the cracking of bones. Mine. Turns out he had thrown his sleeping bag out behind the tank thinking everything was locked in place for the night. But somebody decided to reposition the tank and backed over him. He was in a lot of pain, but still able to talk.

The chopper arrived. A doctor and a medic jumped out, and with the help of platoon members they placed him on a stretcher, loaded him on the helicopter and took off. I knew both the doctor and the pilot. When I saw the doc a few days later I asked if the soldier made it. He said he’s doing pretty well. I asked how is that even possible? Turns out there were three factors: 1- he’d recently had a bowel movement and so his midsection was not rigid when rolled onto, 2- the ground was pretty wet from a daylong rain so he was pushed into that instead of being crushed, and 3- the tank backed straight over him, it didn’t. He ended up with a fractured pelvis and some collateral damage.

Road Marches

We always worried about civilian drivers during road marches. In one instance as the troop was on a public road a car coming in the opposite direction got too close to one of the tanks and its end connectors opened up the driver’s side of the car like a can of sardines. The end connectors stick out farther from the tank than any other part. Fortunately, no one was hurt. In fact, I was never involved in an instance of an injured civilians nor did I hear of any. All our vehicles had what we called “Mox Nix” sticks. They had international traffic control icons on them. We used them to tell civilian traffic when they could pass. “Mox Nix” is GI slang for macht nicht.

Heating Canned Food

Heating C-ration cans of food on engine grates or manifolds was common in cold weather especially. I recall one of my M114 drivers heated a C-ration can of beans and weenies on the engine grate. When it was hot he opened it and blew beans, weenies and juices all over the white interior of his vehicle. For several weeks he was finding contents of the can in strange places.

Umpiring

I also was given an odd assignment for a Field Command Post Exercise. That’s when the command structure moves to the field and maneuvers units through various scenarios. Only there are no units. It’s like playing a board game. In this case it was a Division being tested. I was assigned to sit with the opponent who was reacting to all the division staff’s moves. The lone officer running the opposition, a major, was slowly being pushed into a trap. Finally, he told me the only way he saw to get out of it was to hit the division with tactical nuclear missiles. I asked if they had been approved for this exercise. He said it hadn’t been mentioned. I said whatever you do I will back you. Like a 1st Lt. and a Major could stand up to a division staff headed by a two star general. He gave the command. About 10 minutes later the door to the trailer we were operating from burst open and in marched the two star who asked the major what the hell he thought he was doing. He looked at me and I said, “we are operating under the assumption nukes are in play.” His response was, “no one said they were.” I said, “we may be wrong here, but the major believes the scenario as written didn’t say they weren’t.” The general paused silently for a moment, turned and left.

Porsche & the Polizei

The exercise ended the next day. Shortly after noon I hit the autobahn for the drive back to Fulda. When I exited at Alsfeld, I stopped for gas. Once topped off I continued one a winding two lane road leading to Fulda. I was driving my own car, a Porsche Super 90. It felt good and I let it run. I hit a patch of ice, went into a 360 and off the road to the right, down a bank, to a sudden stop. My car rested at a 45-degree angle. I couldn’t get the driver’s door open. Even breaking the window, if I could, wouldn’t give me enough room to crawl out. The front of the car had hit a concrete kilometer marker and knocked it backward. The front of the car, where the gas tank was, rode up on top of the marker. I tried to scramble to the passenger’s side and open the door. I was worried about a full tank of gas catching fire. I couldn’t get it open.

A face suddenly appeared. He and another man jerked on the outside door handle and popped the door open. They reached in and got me out. Two other Germans joined in as we pulled and pushed my car back to road level. I then determined it would start and though dented could probably be driven. My newly found friends urged me to leave the scene. They said if the polizei came along they would make me pay 20 deutsche marks ($5) for the damages. I reasoned that because of the damage I was going to have to report this to my squadron commander. If he found I skipped out on a fine any penalty would be much worse. So one of them drove down the road, found a phone and called the polizei. Sure enough they came and charged me 20 deutsche marks, gave me a receipt and went on their way. My new friends asked if they could buy me a beer before I left. I declined but thanked them profusely. I reported the accident to my insurance company and squadron commander who suspended my driving privileges for four months. He returned my license on New Year’s Eve. USAA declared the car totaled, so I took the money and pitched in the rest to have it repaired. I shipped it home, drove it from New York to Salt Lake City and had it for several years.

Maneuver Damage

Property damage, or as it was called Maneuver Damage, was a constant problem. One of the reasons tactical testing was done in winter was the ground was hopefully frozen and less susceptible to damage by tracked vehicles. However, in 1965 the weather was so warm the tanks were not allowed in field exercises.

Property damage claims could be filed by property owners or German government officials. Somewhere up the American chain of command a decision would be made as to what damages would be investigated. I investigated a few claims as a “Maneuver Damage Control Officer.” I would meet with the Burgermeister (mayor) or forest manager or whoever’s property was involved and be shown the damage.

In my estimation, the claims repeatedly sought more compensation than the actual repair cost. My sense was that no matter how outrageous the claim, they were pretty much paid without protest by the Army. One of my cases involved a gravel road through a forest. The damage consisted of a few feet of the shoulder being pushed out by a tank track. One man with a shovel could have repaired it in a couple of hours. The request was 40,000 Deutsch Marks, or about $10,000. I recommended significantly reducing the payout. I later found that the Army had paid the full amount.

Courts Martial

A Regimental Legal Officer was available for advice and interpretation of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. The least serious court cases were tried in Summary Court. The cases didn’t require the legal expertise of officers who conducted the trials. The cases had a low maximum penalty. I served these military justice duties: board member of a seven-member board (jury), assistant trial counsel, trial counsel and defense counsel. The last two stand out.

On my trial counsel stint, which I handled solo, there were two defendants, both charged with inciting a fight in a downtown gasthaus that turned into a racial brawl. Enhancing the situation was coverage by the Overseas Weekly, a privately owned newspaper that focused on the American military in Europe. It was not reticent about carrying negative news. The charges in this case were indeed serious. How it became only summary court case I didn’t know but the why I was pretty sure about. The brass wanted it out of sight and thus out of the news. So the charges were something like “using language to incite public disorder.”

After days of preparation and interviewing witnesses, I knew I was going to lose. On the first day the defense counsel moved to separate the trials. A smart move. I decided to try my strongest case, more aptly my least weak case, first. After the first two witnesses, it was apparent what was happening. Principles had gotten together and locked down their stories. No German witnesses had been deemed knowledgeable enough to testify. I lost big.

The next day number two was on trial. After thinking about it overnight I made a motion to dismiss the charges. The president of the board quickly agreed. Game over. Well, not quite. I was dragged into the Squadron XOs office and roundly chewed out for not first clearing that decision with him. He said he was going to hold up my promotion if possible. I didn’t say much and left the office. I knew he would have to get permission from the squadron commander and the regimental commander to stall my promotion. I went to the Regimental Legal Officer and laid out what had happened. He told me not to worry. A few days later he said the regimental commander told my squadron commander that I had done the right thing.

My last appearance involved a soldier charged for fighting with several Germans. The two buddies with him managed to escape before MPs arrived. He was scooped up. He pled not guilty. On my first meeting with him he made it clear that he wanted enlisted men on the trial board. That was his option, generally considered unwise. The theory was they would be senior NCOs and would be harder on him than officers. He insisted. So into the fray. We walked into the room and saw one captain, five first sergeants, all from line units, and a senior master sergeant.

The prosecution opened and proved incapable of asking a question that was not leading. “Objection your honor.” Occasionally I would let one slide if I knew the answer would provide information helpful to the defendant. We were working through an interpreter which gave me more time to react. The witness, one of the German participants, did manage to identify the defendant, only because he was sitting at the defense table. But he couldn’t even vaguely describe those who fled. I asked if the person in the fight was in uniform the night it happened. The witness said he didn’t think so. I pointed out it was awfully dark with only a nearby dim streetlight for illumination. So “is it possible you could be mistaken.” He said he didn’t think so. I rested. My closing was short. Basically there was no solid identification. I pointed out my client was an American Indian and there were thousands of workers from Italy in town working on construction projects. Many had similar complexions as the defendant. Maybe it was one of those he saw. I also said I had lived in the American West most of my life and thought even I would have a difficult time in some cases, under the lighting conditions that existed, differentiating some Italian workers from the defendant. We rested and left the room. About 20 minutes later we were called back. I could see faint smiles on a couple of panel faces. Then the verdict. Not guilty. Finally, a victory. Later the Squadron XO asked what law school I went to. I told him the University of Perry Mason. I don’t think he quite caught the joke.

Personnel Personal

When my soldiers had personal problems, I usually got involved. For example, a Specialist 5 with a wife and three kids had credit payments of at least $200 a month more than his monthly take home pay. I helped him figure out how to climb out of debt. I knew the answer: cut down expenses. I did not know how to advise him to do so. I finally took him to our Regimental finance officer and asked him to help. He did. You may ask why was he allowed to get in so deep? There’s no official answer. But it was not unusual for lenders to be less than thorough about checking credit of American soldiers. They knew if payments weren’t made that could be reported to the commanding officer and it would end up on someone’s desk for a solution.

Another uncomfortable duty for platoon leaders was having to give permission if a soldier wanted to marry a German citizen. I had one such case. I didn’t have the faintest idea what to do, so I tried to be honest with him. He was a bright sergeant who commanded my mortar squad. The unit never failed to finish first in any competition. He was also an outstanding athlete. I asked how her parents felt about the relationship and a lot of stuff that would probably be prohibited today. It may have been then also but who knew? I finally got to the most troublesome issue. He was black, she was white. I asked if he had discussed the problems that might entail, particularly when in the U.S. He said he had. I said, “you realize that most of the posts you might be assigned to would be in the south?” He did. So I gave my permission.

Extra Duties

Every lieutenant it seems performs Squadron Duty Officer (SDO) and Officer of the Day (OD) duties. The SDO basically answered the Squadron HQ phone overnight and moved anything important on to the appropriate officer. The SDO also was the person who got the call when an alert from higher headquarters was activated. But most of the time was spent trying to get some sleep on a rickety old cot.

One of the tasks of the OD, in addition to posting the guard and checking on base security, was stopping by both the NCO and Officer’s clubs. The primary duty at both places was to watch as the money from the slot machines was counted, put into a money sack, sealed and then locked in a safe. Both the NCO doing the counting and OD had to sign a receipt certifying the amount in the bag. The bonus of this duty was the inevitable free steak dinner at the NCO club.

Junior officers also were on rotation as Mess Hall Officer. We were required to report on several things, the most important was the quality of the food. I probably pulled this duty three times during my tour. I used a technique of standing in line with the troops. I then ordered what the soldier in front of me ordered. I would then switch trays with him. Afterwards I’d ask him what he thought. He normally groused about taste and quality a little but admitted it was edible. It was not an unusual comment. Some would be more severe, others more forgiving. I would also circulate among the tables and talk to other soldiers. The response was generally okay, but not enthusiastic. My own opinion was it was a quality meal with a variety of food choices. After my second turn as Mess Officer it dawned on me what the problem might be. The mess hall was a large building with grayish green interior walls and a high ceiling. It was extraordinarily bland if not depressing. I would lose my taste for the food too if I ate three meals a day there every day. I put that in my report. Somebody actually read it. The next time I was in the mess hall it had been painted in bright colors. A stereo system had been installed. I was told that music selection responsibility rotated among the four cavalry troops, artillery battery, engineering company and other units on a weekly basis. The only difficulty was the spirited discussion that occurred in some units when deciding which music to provide. Just as there were a variety of backgrounds, both ethnic and sociological among the troopers, there were a variety of musical tastes.

Every junior officer also had Pay Officer duty for his troop. I’d draw my Colt M1911 .45 caliber semi-automatic pistol from the armory, strap it on, go to the finance office and sign for a whole bunch of money. Everyone was paid in cash in my day. I would sit at the pay table, soldiers would come by and I’d count out what they had coming. If the troop had men manning the border, I would go out and pay them. The rule was everyone got paid on pay day. The money had to go directly to soldiers. No one could pick up money for him, not even a wife. The pay officer had to account for every last cent at day’s end.

Living on the Economy

In early 1965 three other lieutenants and I moved from the Bachelor Officers Quarters on the kaserne into an apartment in Fulda. It was on the edge of the main downtown area. It had two bedrooms with two beds and two dressers each, a large living room, a small, but efficient kitchen with a gas stove and a bath with a tub/shower and of course a toilet with the water tank located on the wall above. It occupied the entire third floor of what was a smallish business establishment. The first floor was a gasthaus, the second living quarters for the landlord and his wife and the third floor was the rental apartment. Moving was my best friend’s idea. I suspect he was motivated in no small part by the fact it wasn’t too far from a woman he was serious about, Gisela Asbrand. They later married and settled in Cleveland. My motivation was each share of the rent came to $25 dollars a month. The housing allowance we got for living off post was $125 dollars a month. My first few paychecks were gross $222 a month, net $199.

The apartment was in a great location, not much of a drive to the kaserne and an easy walk into town where we frequented the family owned bakeries and the farmer’s market on Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings.

Around the corner was the main Catholic Cathedral (Dom) with appropriate bells. They inhibited sleeping in. The Dom was commonly referred to as the new cathedral. It had been built around 1200. Next to it was the old cathedral, Michaelskirche, which dated to 900 AD. It is the oldest functional church in Europe. One of my friends was married there.

My favorite bar: Pferdestalle (Horse Stable). It had been a horse barn at one time. It was a college age kind of place and many there were my age. It had a more than passable rock band. In fact, the first time I heard a Beatles song (early 1964) they performed it.

Favorite restaurant: The Café Zum Rollingswald, in a wooded area outside town. It was a primary target after I had been in the field for a while. I always ordered the Weiner Schnitzel, large and tender, with a huge bowl of salad served family style and French fries. It almost doesn’t need saying that the beer was good.

The Kreuzberg Monastery: On a hilltop, as the name implies. The monks who live there sold home brewed beer, cheese sandwiches on bread baked by the brothers, books and souvenirs. And they ran a plattepulle (ski lift). The trip down the winding road was much slower than the drive up.

Favorite hotel: The Zum Ritter, about a block from where I lived. It had a restaurant, several floors of rooms and suits of armor scattered around and reeked of a much earlier time. I finally stayed there in 2011 when I went back with my wife Evelyn and spent a week reliving old times with Ed and Gisela.

But the best place of all was the home of Gisela’s mother. She invited me to Sunday and holiday dinners and parties. I always felt welcome. Those were warm, festive and memorable times; to use a German word, Gemütlichkeit.

In Retrospect

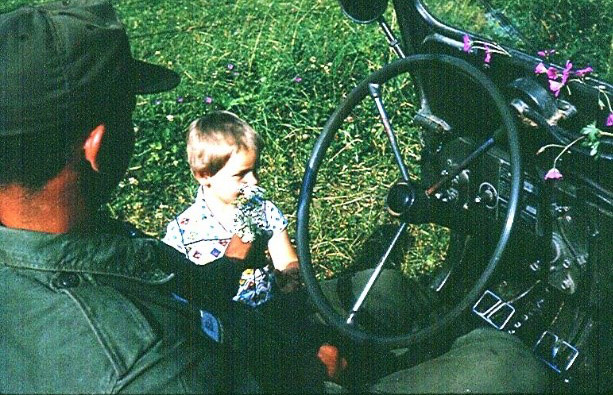

One of my more poignant memories were days when families separated by the border would gather on either side and catch up with each other’s news by yelling across the barriers, minefields and barbed wire. One Sunday morning I came around a curve to check on a road barrier and saw a family of three adults and two children gathered there. After checking with the German border guards (and getting permission from their dogs), I went to talk with the family. They were hoping their family members on the East side of the border would soon appear. As we chatted, the youngest child, a girl five or six years old, picked some flowers from a nearby field and presented them to my driver PFC Gary Batchelor. To this day the memory is a reminder of why we were there.

Dedication

To Sergeant First Class Al Cash, my Platoon Sergeant for most of those months. You were the best. (He later was promoted to First Sergeant.)

To all the soldiers, draftees and volunteers, who came and went from the first platoon. You came from all corners of the United States with varying ethnic identities. In fact, the platoon was more than 50% minority. I learned a lot more from you than you probably did from me.

The 21 months I was a reconnaissance platoon leader in the 14th Armored Cavalry were the most formative time of my life. I joined the platoon as a young 22-year-old and left as a much wiser, but still young 24-year-old.

John S. Edwards

2nd to 1st Lieutenant

Platoon Leader, C Troop & S-3 Liaison Officer

1st Squadron, 14th Armored Cavalry

January 16, 1964-January 31, 1966

Discharged Fulda, Germany, Feb. 1, 1966